As the end of March approaches, we have reached both the first anniversary of Britain’s coronavirus state of emergency – and at the same time the end of this blog. We have kept this diary for a year now, first daily, then weekly, and now monthly.

The past year has seen the enforcement of the coronavirus state of emergency fundamentally undermine the myth of “policing by consent”. With its draconian new Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, the government appears to want to destroy it completely.

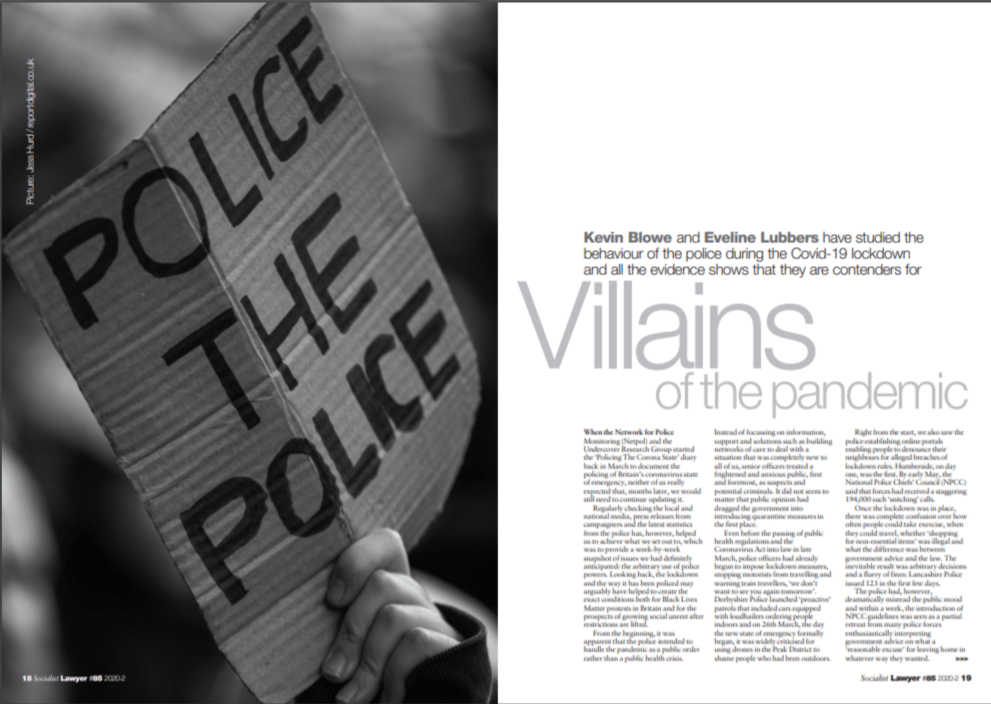

In January, the police complained they were seen as “the villains of the pandemic” – that was partly because of our work. Last month, we warned against the “Slow Building of an Emergency State” in Britain. It seems as though the police have learnt little since.

While there is – unfortunately – still more than enough to report on, there are others that keep an eye on the issue, Big Brother Watch and the various lawyers that we’ve been working with.

On a lighter note, this final post appears with what seems the start of Spring – and the further lifting of some of the restrictions that came with the most recent three month lockdown.

POLICING

In England from 29 March, more outdoor activities as permitted by government regulations and the ‘stay-at-home’ rule is lifted. In the aftermath of public backlash against police cracking down on protests (see below), these are now exempt from restrictions on large gatherings, as long as they are organised by a public body, business or political body or other group. Organisers are also required to undertake risk assessments (with all the continuing concerns about the police’s lack of experience in assessing public health risks, which we highlighted here again and again), as well as maintain social distancing.

As the first anniversary of the first lockdown approached this month, in many respects little has changed since this time last year, with the police continuing to confuse the law with government guidance. Contrary to what police forces in England keep saying, there has been no outright ban on public gatherings and the police remain obliged to consider human rights laws, when deciding how to interpret the regulations.

As lawyer Pippa Woodrow emphasised, police permission isn’t a legal pre-requisite to a protest being lawful, and police do not have a general discretion to permit or refuse to allow protests. Proportionality assessment is a legal question which can be challenged.

In practice, the opposite has been true. In Manchester, the organiser of a protest against the government’s controversial 1% pay rise plan for NHS staff in England was fined £10,000 by police. The rally in city centre on 7 March at midday was attended by about 40 people. The organiser was woman who works for the NHS, aged 61. Another NHS worker, aged 65, was arrested for failing to provide details after initially refusing to leave. She was de-arrested and fined £200 after complying, police said.

Meanwhile in Scotland, on the same day, police worked tirelessly escorting the Rangers fans to make sure they made it safely from Ibrox to George Square to celebrate winning the league.

A week later, faced with a legal challenge from organisers for a planned protest in memory of Sarah Everard, where the suspect in her murder is a serving Metropolitan Police officer, the force admitted that its position that its “hands are tied” by the coronavirus regulations was incorrect and it did not have a “blanket ban” on all protests. Nevertheless, after the High Court refused to intervene, subsequent negotiations fell through and the vigil’s original organisers were forced to cancel the event. Inevitably, with mounting public anger over the murder, a gathering went ahead anyway at Clapham Common on 13 March and led to scenes of arrests and confrontation that were widely condemned.

On 30 March, HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, Fire and Rescue released a report on its investigation into the policing of the Sarah Everard memorial gathering. It concluded the police response was “appropriate”, because even though the Metropolitan Police had been wrongly interpreting the regulations in the past, it was obliged to act in a consistent way. This assessment is unlikely to convince any of the critics of the way the police responded to the vigil.

Since that crackdown in mid-March, a growing movement has condemned police intolerance to the right to protest and warned this will only become worse with the passing of the government’s Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill. Protests in Bristol and Manchester have been restricted based on justifications of the need to protect public health and in Bristol, recurring demonstrations have been met with an increasing violent response.

In Manchester, Manchester Evening News reported that at an initial demonstration on 21 March, police did not intervene with protestors. However, 15 people called Green and Black Cross Manchester to report they had been issued Fixed Penalty Notices (FPNs). The majority of these related to attendance, but at least one person has been threatened with a £10,000 fine for being an organiser of the protest, according to Netpol. The following week, the police response to a further demonstration was more confrontational, with accusations that officers had assaulted teenagers. One arrest, involving a young person whose clothes were almost pulled from her body, is now the subject of an internal police investigation after a photo was circulated by Reuters.

Meanwhile in Manchester and Sheffield, students have accused their universities of granting police officers access to halls of residence to check for breaches of coronavirus rules, sometimes in the middle of the night. The Guardian heard about regular police patrols and widespread use of fines of up to £800 as universities clamp down to avoid major coronavirus outbreaks now that students are returning for the spring term.

Students say they believe that in some instances police officers may have received keys from university security to enter flats unannounced and check that students were not socialising with their neighbours. The universities have denied this.

Meanwhile, dozens of people performing doing a HokeyCokey dance in Alexandra Park in Hastings on 15 March, were dispersed by the police. No covid fines were issued, though many were not wearing masks and 1,5 distance was not kept.

NEW REGULATIONS

The government released a new set of regulations, another 93 pages that for the first time were published ahead of implementation. Michael Maggs started summarising, and barrister Adam Wagner has a first overview of what the plans mean. “First thing to say: this is another completely new system. We have had national restrictions, local restrictions by separate regulations, the first lot of Tiers (1-3), a second national lockdown, new Tiers (1-3+) then Tier 4 added, third national lockdown. Now we have… Steps.”

Big Brother Watch warns against the Government’s report on the Coronavirus Act because it says Schedule 21 power to forcibly detain, quarantine and test people, including children are “essential” in the “long term”. The report also says extreme Schedule 22 powers, under which Ministers can issue directions to ban protests & gatherings, “may be used” as we “move through the roadmap”. Big Brother watch urges people to lean on their MP to get rid of this law.

RESOURCES

* Fixed penalty notices during lockdown “allow the police to operate as both judges and as jury, with no appeal courts able to intervene”. Here’s lawyer David Renton’s advice on what to do if you get one.

* Justice Nowhere: Racist Policing Under Lockdown– Ken Hinds via YouTube. Hear from Ken Hinds, Chair of Haringey’s Independent Stop and Search Monitoring Group speak on the use of force and strategies to hold police forces accountable.

However, on 30 September, MPs

However, on 30 September, MPs